The first time Suzanne Asbury-Oliver flew a plane, she was 14 years old. That was the easy stuff, in a sailplane, back when she could actually see in front of her.

As a skywriter for Pepsi, Asbury-Oliver spent 25 years crafting messages with smoke in the sky, frequently taking her dog along for the ride in the front seat. She flew an antique biplane, which completely obscures one’s line of vision. That means she’s writing the mirror image of words at 10,000 feet above Earth, effectively with her eyes closed. “It’s seat-of-the-pants-type flying,” she says.

Now, without a corporate sponsor, she and her husband own their own plane and skywriting business called Olivers Flying Circus. They received plenty of requests in the leadup and aftermath of Nov. 8 — yes, just like the ones you’re imagining — but Asbury-Oliver refused, on a no-negativity principle.

Since letters only last in the sky about 10 minutes, the beginning of a word will sometimes disappear by the time that word is finished, but Asbury-Oliver doesn’t worry about that. “It’s like a ticker tape; you know what it says even if the first letters are gone,” she says. Or, more fittingly, like an original Snapchat — except, of course, that anyone within a 20-mile radius can see it if they simply look up.

The most crucial lesson Asbury-Oliver has learned from a career in skywriting is survival. “Never fly straight over a swamp,” she advises sagely. “If you have an engine failure and end up going down, nobody will find you, except the alligators.”

Age: 57

Based in: Tucson, Arizona

Graduated from: I finished high school and a few college courses. Flying lessons are very expensive, so I had to decide between college and flight training. I made the decision to be a professional pilot and got my pilot’s license.

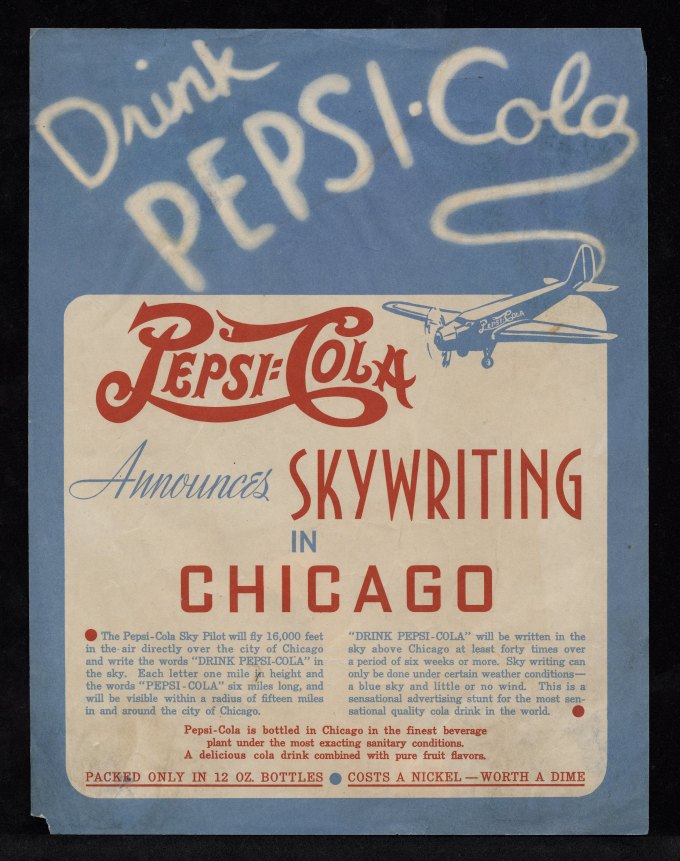

Years in the business: I started flying sailplanes at age 14 with my dad. I began a career from it in 1980 by teaching people to fly. I was burning out on that, so when Pepsi-Cola ran an ad looking for someone to fly a skywriting plane for them, I applied — along with about 2,000 others. I got the job. A 70-year-old gent named Jack, who doing it at the time, taught me how.

How did that differ from your previous flying experience? The airplane was an antique biplane, which was built to be flown out of grass fields. But I had to fly it off concrete runaways. You can’t see anything in front of you, so getting comfortable with that was my first challenge.

So what were those flying lessons like? The plane was single-control but had tandem seating, so during my first skywriting flight, I sat in front — the pilot was in the back in a separate cockpit. There was an intercom system between us, so Jack described what he was doing. I figured we’d do that for about three weeks, but after that first flight, we landed and he said, “OK, your turn.”

What was your reaction? “Holy crap, you’ve gotta be kidding me.” You can’t coach someone from the ground, but he stood below and drew what I was writing in the sky. That way, when I landed, he could show me where to improve, and which turns to tighten up. You can’t really see what you’re writing while in the plane.

What tactics supplement for not having a line of vision? You have to know from experience what types of turns to make, so you don’t run over the last letter or space them too far apart. That’s the hardest part: maneuvering around to get in position for the next line or letter. I count to myself to measure the size of letters. You’re maneuvering the plane like a pencil on paper. Some parts of the country have section lines, and we can use those as a grid for a ground reference, but choosing one specific mark on the ground doesn’t work because of the winds. It takes a lot of practice; it’s not as easy as it looks.

Oh, I don’t think it looks easy at all. I’m also on top of the word while writing it, and the audience is beneath, which means I have to write the mirror image of what’s being seen on the ground. I spend a lot of time on the ground thinking it through and charting the most efficient path. You have to consider the sun angle and where in the sky to write the words so it’s most visible to whoever’s paying.

How long does a message last in the sky? My record — on a good day with smooth air — is around one hour and 40 minutes. Everyone thinks the wind is our enemy, but it’s really the clouds or haze. There needs to be a good contrast, with a bright blue background. On average, a letter stays legible for about 10 to 15 minutes. It takes about 10 minutes to form seven letters, so if the message is longer than that, the first letter starts disappearing as I’m working on the rest.

What substance is used to form the letters? It’s a super lightweight oil with a paraffin base. We carry 27 gallons of it in a tank in the front cockpit. A pump is connected to a trigger on a stick — the same stick we use to fly the plane — that we can turn on or off. The fluid is injected into the exhaust system of the airplane at the exit. The temperature is super hot, so it vaporizes the lightweight fluid. We call it smoke, but it’s really a vapor.

Some of the weirdest message requests: One time, an artist wanted us to draw a cloud. Another time, a woman wanted us to write a message about a going-out-of-business sale in New York City, a few days before the anniversary of Sept. 11. Her message was “Sale – going out of business – last chance.” People saw “last chance” and went nuts. They thought it was about an attack. We also got all types of horrible requests during the 2016 election, but I wouldn’t do that. [Skywriting] supposed to be fun and happy, and make people smile.

What happens when you make a typo? Mother Nature is our eraser. The most common mistake is getting distracted: You’re talking to air traffic control and lose track of which letters you’ve already done. Once, I wrote three “P”s in Pepsi, and afterward, I joked that I was just stuttering. But I don’t think I’ve ever gone up and spelled something incorrectly. I double check everything beforehand, because I’m the worst speller in the world.

Do the messages reflect your handwriting at all? No. My skywriting is much better than my handwriting.

Is any airspace restricted for skywriters? The Super Bowl has restricted airspace, but that only goes up to 3,000 or 5,000 feet [above the stadium]. So it doesn’t affect us; we fly above that. There’s also a presidential temporary flight restriction, which is a ring around wherever the president is.

Altitude for skywriting: Usually between 10,000 and 12,500 feet.

Size of the letters: Each is about half a mile to three-fourths of a mile. The whole word stretches five to 10 miles across the sky, and a message will be seen for at least 20 miles, on a good day. We can do up to 25 letters in one flight.

Putting aside your fearlessness, let me ask a more logistical question: Do all the sharp turns make you nauseous? No. But the smoke has a little bit of an odor, and mixed with the constant G-forces… I just tighten my muscles to keep the blood in my head.

What it costs: The most expensive part is getting the plane to each customer’s location, which costs us $2 per mile. Once we’re on site, it depends how much the customer wants written. The least amount we’d charge — without any mileage attached — is around $2,500.

That’s not cheap for something so temporary. I think more people are requesting it now because of the social media aspect, and being able to record and share it. A message may stay in the sky for just 10 minutes, but with all the smartphones, it lasts forever. Companies see the value in that, too, and will do a hashtag to capitalize on it. We’ve gotten more personal messages over the past few years. Usually, we get some feedback from those, once the excitement wears off a day later. We’ve had couples approach us at air shows years later, someone we wrote “Marry Me” for, and tell us they’re still together.

Financially speaking, how did you make a career from skywriting? I think I’m the only person to make a living over the course of their career skywriting. I was doing skywriting for Pepsi for about 25 years. When that sponsorship ended, in 2000, the plane was donated to the Smithsonian with my name on the side and my dog’s name on the front cockpit — she flew with me all the time. Right now, though, my husband I are doing it on our own, which we can do because we built up a client base and reputation over the years. But we had Pepsi’s help to save money to buy our own plane, a Super Chipmunk plane called SkyMagic was originally built for the Canadian Air Force.

Best part of the job: The people I’ve met over the course of my career, and the travelling we’ve done. Sometimes, when I land, a little kid will run up and say, “You wrote right over my school!” or “I was in my backyard and saw that!” They think it’s done specifically for them.

Most challenging part of the job: The travel and the weather. It’s frustrating when you travel 2,000 miles for a job and it gets rained out or clouded out. That’s why we try to talk people into giving us a window of two or three days.

The toughest letters to write: The “W” — the kind with straight lines, not curves. You have to turn around after three-fourths of a mile and get back at that exact ending point for the next leg. The chances of getting all those angles exactly right is really tough when you can’t see them. The “S” is also tricky, because the plane is decelerating as you turn; you have to change the angle to match the deceleration to make both halves curved the same amount.

Has the flying gotten less exhilarating? The skywriting part is the reward for the other hard work, like fighting the weather and driving around with our motor home. Every flight is different; the temperature, audience, and weather are different. So it never gets routine.

Does skywriting require any certain qualifications beyond a pilot’s license? The airplane has to be very specific, with the smoke system all set up. But there’s no school or book to teach yourself. It’s passed on from skywriter to skywriter. That stems from the old days, when the first skywriters were competing with each other and wouldn’t share their techniques. My husband and I are mentoring a young man who does most of our traveling, like the transporting of our plane around for different jobs. We’ve done work all over the country and the world, including Puerto Rico, El Salvador, Alaska, Mexico, and Hawaii.

Most crucial lesson you’ve learned on the job: How to survive, I guess. [Laughs.] I’ve had two engine failures. You learn to be smart about decisions you make and not take unnecessary risks, like not flying in unsafe weather to get to an event on time. We’ve lost a lot of friends in this business who pushed the weather one step too far.

Your trademarks: A smiley. I do a circle for a head, then come back in for the eyes and mouth. Making a perfect circle — hitting the same point where you started — is tough, but it’s a matter of practice and learning the airplane.

LAUNCHING YOUR CAREER>>

1. If you’re intrigued by aviation and flying, there are so many different options. You don’t need to just be at the front of an airliner. Lots of career opportunities are behind the scenes.

2. Go work for someone in the business, and be their crew chief or drive their trailer. Get a realistic look at how hard it is.

3. Skywriting is much more than just flying your own plane and having the right equipment. You have to be able to run your own business and manage your own finances. It’s a huge investment, with a lot of capital upfront for the equipment.

For more badass female No Joe Schmos, meet the woman revolutionizing airbrush tanning and the woman saving the rainforest in $8 rubber rain boots. All images courtesy of Olivers Flying Circus unless otherwise specified.

Fascinating post, and so timely for International Women’s Day!

Sent from my iPhone

>

[…] ← Previous […]