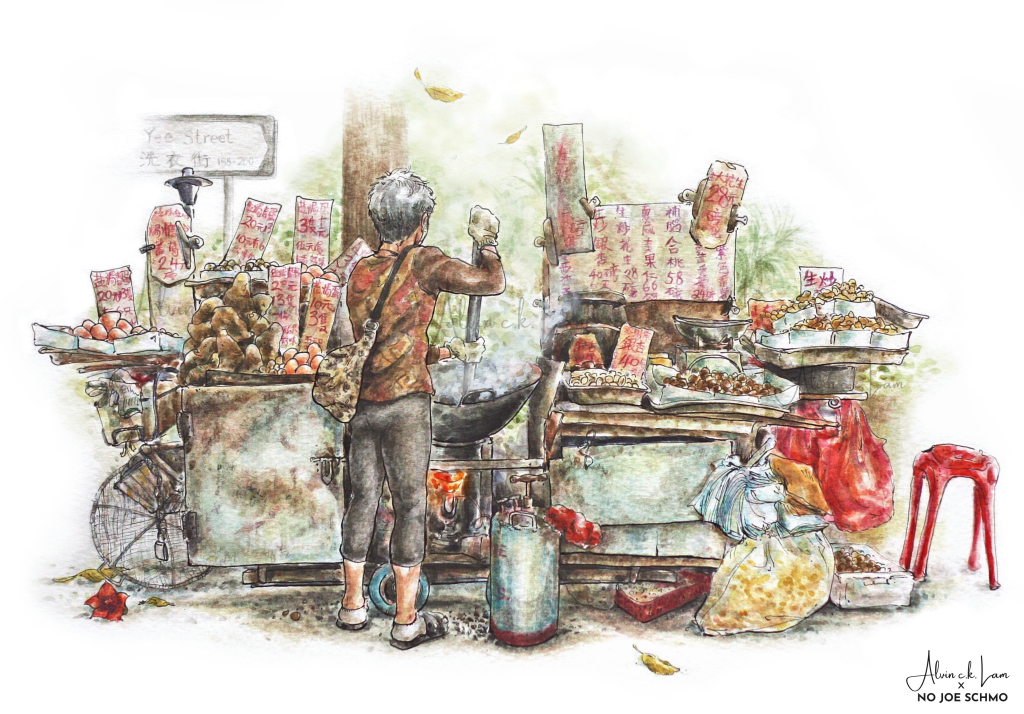

Forget what you know about minding your own business. For a group of women who operate in the depths of one of Hong Kong’s most chaotic neighborhoods, their business is your business. They help you seek vengeance on conniving coworkers, evil bosses, and cheating husbands.

There’s a highway overpass in Causeway Bay near the city’s central business district that you’d very likely hurry past on your way to work or brunch without a second glance. It’s filled with incense fumes and trapped humidity – and five stalls, each manned by a woman in or around her 70s engaging in da siu yan (打小人), or “villain hitting.” It’s a kind of folk sorcery popular in southern China and Hong Kong, perhaps most conveniently compared to voodoo.

Ms. Chiu describes her job as worshiping gods. Which, technically, is true. But almost within the same breath, she casually mentions in Cantonese that she’ll curse the day your husband’s mistress was born or make sure your petty brother never succeeds in business. For a fee, of course.

Continue reading “The Villain Hitters of Hong Kong”